Ulster Nationalism presents the solution to the 'British versus Irish' identity issue in Northern Ireland (referred to as Ulster from this point). It aims to remove both the 'Brits' and the 'Irish' from Ulster by establishing a common cultural identity that bridges the religious divide. This approach carries political benefits for our people and is economically viable. In this introductory article, we, at the ULI, will outline some of the fundamental features of Ulster Nationalism and its history.

In essence, Ulster Nationalism advocates for the independence or increased autonomy of Northern Ireland, rooted in a desire to protect and promote the distinct cultural identity, heritage, and interests of the Ulster folk.

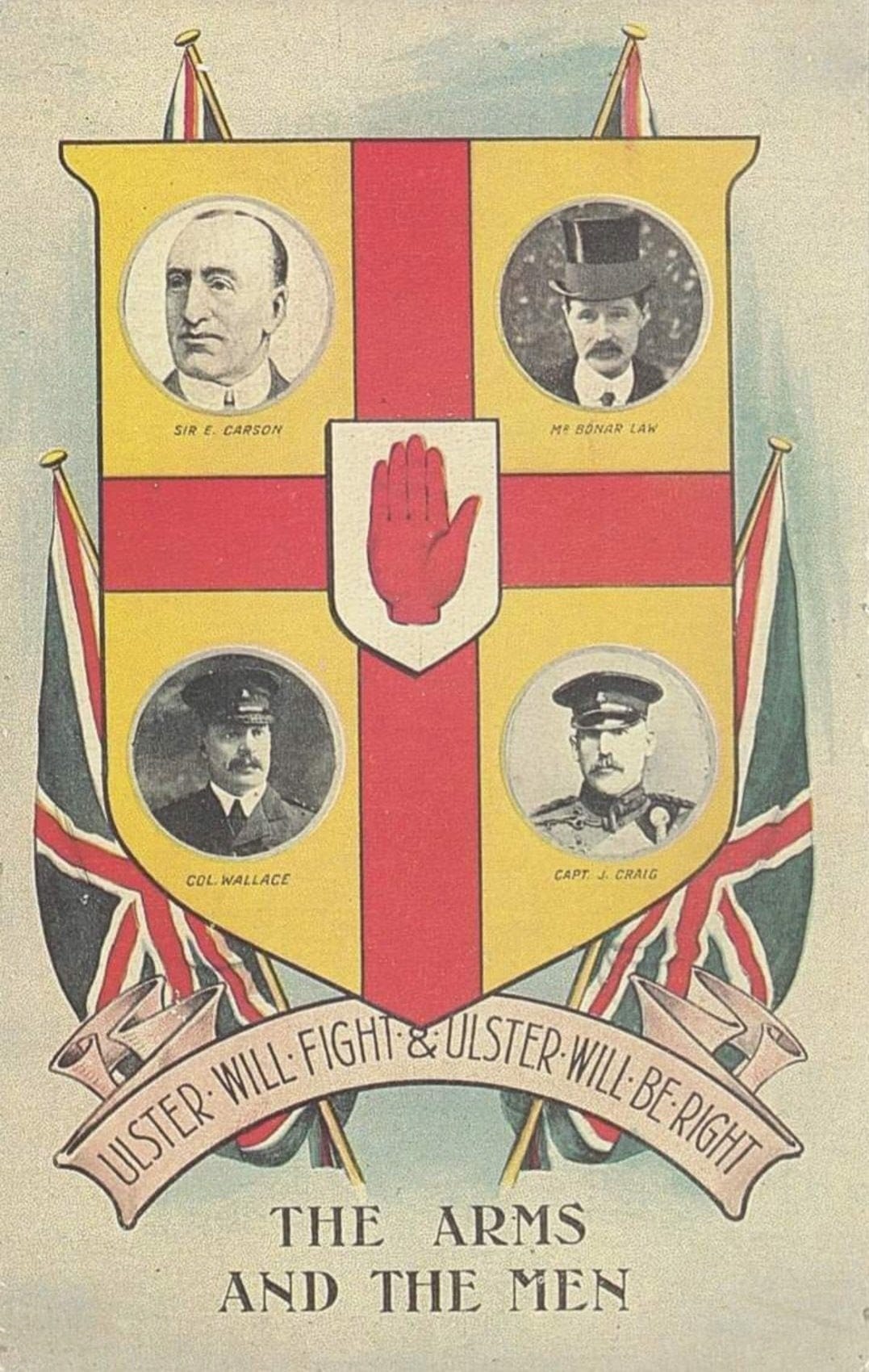

How does Ulster Nationalism differ from Unionism? Unionism has dominated the ideology of the Ulster folk for the last century and a half. Intensified by the three Home Rule Bills, with the third leading to the creation of the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. Unionists see themselves as British, prioritizing their British identity and aligning with political and cultural ties to Britain. In contrast, Ulster Nationalists believe in the true meaning of Quis Separabit: '‘… ‘Quis Separabit,’ meaning that nobody shall separate us from our province.'‘ – Brig. Andy Tyrie.1

How do we plan to achieve this? Through a strong emphasis on the distinctiveness and autonomy of Northern Ireland within the island of Ireland. Ulster Nationalism advocates for the protection of Ulster's cultural and political identity, as well as the promotion of its economic interests. Ulster Nationalists believe in the right of the people of Northern Ireland to determine their own political future. Our ability to look after our own affairs is fundamentally compromised by being a member of the Union – just look at Direct Rule during the 'Troubles.' This can be rectified by Ulster becoming legislatively independent.

The history of Ulster Nationalism can be traced back to the mid-20th century with W.F. McCoy. Serving in this capacity for two decades, from April 12, 1945, until 1965, McCoy, born in 1885 to a Methodist family in the town of Filemiletown, emerged as a pivotal figure in Ulster Nationalism. While initially conventional, McCoy eventually recognized a fundamental flaw within the Union: Ulster rested in the hands of individuals from an opposing island. Our Ulster could easily be forced into a United Ireland (similar to how Britain imposed the Windsor Framework on us!). His proposed solution? Dominion status for Ulster — a sentiment also endorsed by Prof. Kennedy Lindsay. Despite retiring as an MP in 1965, McCoy remained dedicated to the cause, consistently articulating and endorsing the concept of Dominion status for Ulster until his passing in 1976. It is important to note that Lord Craigavon did suggest Dominion status to Lloyd George during 1921 however it only became a concentrated effort under McCoy.

We then have the Ulster Vanguard. William Craig, founder of the Ulster Vanguard (VUPP), believed that Ulster independence could guarantee the British way of life in Ulster as the threat of Irish unification loomed, and Protestants would be discriminated against.

A person who slightly differed from this view is Professor Kennedy Lindsay, who as previously mentioned, called for the Dominion of Ulster. Dominion hood over independence does have its benefits and either are preferable to our current situation. Prof. Lindsay most loudly supported the creation of a Dominion of Ulster in the Ulster Vanguard Publication: “Dominion of Ulster?”.2 This is a 1972 booklet that puts forward the call for the Dominion hood of Ulster. As the Professor writes in the introductory paragraph:

“The Ulster people are in the post-Munich situation of the Czechs. They have been betrayed and humiliated and know that a large section of the mainland politicians are keen to purchase "peace in our tine" either by immediate or eventual secession of the region to the Irish Republic.”

Another group that would put forward Ulster independence was the Ulster Political Research Group – later called the UDP. This was the political think tank of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA). The UDA embraced Ulster Nationalism and the flag of Ulster Nationalism can be seen on their murals, artwork, interviews, banners, etc. The defining document of the UPRG would be “Common Sense”3. This is one of the first attempts by Loyalists to breach the religious divide and find the answer to Ulster. Sadly, it fell on deaf ears.

One individual who supported Ulster independence, even if for a short time, was Lord Trimble. Former leader of the UUP and one of the signatories of the GFA (for good or worse), Lord Trimble expressed Ulster Nationalism in his booklet 'What Choice for Ulster?.' Sadly, no digitized version exists, but the booklet is present in the archives of the Linen Library and in the Queen's archives. Some excerpts of the booklet were published online by Ulster Third Way in the 2000s4

Another key individual who supported Ulster Nationalism is Dr. Ian Adamson (1944 – 2019). Dr. Adamson was a former Lord Mayor of Belfast, UUP MLA for East Belfast. In 1988 he was given the OBE by the Queen and also served as the High Sheriff of Belfast. Not only this, he also founded the Ullans Academy, one of the founders of the Cultural Traditions Group; Ultach Trust and also served as a member of the Ulster-Scots Agency. His works mainly explored the Cruthin – pre-celtic inhabitants of Ireland. Through this – alongside embracing the Ulster-Scots and Ulster Gaelic roots of Ulster – he felt the religious divide could be broken and the Ulster culture we all crave could be created. Celt-supremacists like to smear him, but he already defended himself in his article: “The Academic Suppression of the history of the native British or Cruthin, the People of the Pretani” which can be read on his website.5

Through our goal of creating an Ulster culture, we will embrace Ulster Gaelic but also Ullans (Ulstér-Scotch). Instead of our children being forced to learn English and a modern foreign language (e.g., French or Spanish), Ulstér-Scotch will be the primary language and English the secondary. Ulster Gaelic being seen as a language they can learn by choice. We do not seek the active removal of English from the Ulster way of life, but this is an effort that we feel is necessary for the Ulsterification of Ulster.

Economic aspects of Ulster Nationalism will only be summarized briefly here. Many smaller nations, with smaller GDPs, survive despite being independent. As Robert K. Campbell wrote:

“The glib assertion that an independent Ulster would in any case be economically unviable is far from proven". In fact, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of' Northern Ireland, (which is approximately US$13,500 million) is substantially larger than those of many independent states. Even if one assumes that an independent Ulster will have a GDP of only 60% of the above figure that is, around US$8,100 million - it will still be greater than those of states such as Estonia (Gross National Product - GNP - which is often greater than GDP, of US$6,088 million), Costa Rica (GNP: US$5,342 million), Croatia (GDP: US$7,500 million), Cyprus (GNP: US$6, I 35 million), and Kyrgyzstan (GNP: US$6,900). Not to mention countries such as Andorra (GNP: US$1,062 million), The Bahamas (GNP: US$2,913 million), Barbados (GNP: US$1,680 million), Jamaica (GNP: US$3,365 million), Malta (GNP: US$2,598 million), Namibia (GNP: US$2,051 million), or Nicaragua (GDP: US$1,897 million) to name only a few. Note, if an independent Ulster's GNP is greater than the assumed GDP of US$8,100 million, it would put the same country in the same league as oil rich Ecuador (GNP: US$10,772 million), as Kenya (GNP: US$8,505 million), Latvia (GNP: US$9,193 million), and Lithuania (GNP: US$10,220 million )12. Of course, independence would involve sacrifices, as independence has done for Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia and Slovenia. But it should not be forgotten that the creation of Northern Ireland demanded significant economic sacrifices: our traditional main market for many of our products and services, such as banking, distilling, baking and tobacco products, namely the rest of Ireland, was cut in half between 1920 and 1924 by Irish boycotts and sanctions.

Ulster Nationalism has profound political implications, often centering on the constitutional status of Northern Ireland. Some proponents of Ulster Nationalism seek a more authoritative devolved government, demanding greater decision-making powers and autonomy from London. Others aspire for a closer union with the Republic of Ireland, viewing a united Ireland as a means to safeguard their cultural and political interests.” 6

In conclusion, Ulster Nationalism aims to address the longstanding challenge of navigating divergent identities by establishing a common Ulster culture that transcends religious divides. This cultural emphasis serves political, cultural, and economic purposes, fostering unity and autonomy while promoting the distinct identity, heritage, and interests of the Ulster folk. On the economic front, Ulster Nationalism challenges assertions of economic unviability by highlighting the potential for an independent Ulster with a GDP comparable to or surpassing that of many independent states.

Quis Separabit?

Figures wont be accurate to modern day as this was wrote in 1995. For the source see here: